Digital Wellbeing Apps as an Intervention for Mobile Phone Overuse: A Preliminary Overview

Download Original Google DocIntroduction

The use of mobile devices has become ubiquitous in recent years, leading parents, educators, and policy makers to question the potential negative effects of overuse. Numerous studies have noted a correlation between increased mobile phone use and decreased executive functioning, prompting a surge of interest in the use of digital wellbeing apps to mitigate mobile phone use. This paper will review design principles contributing to mobile phone overuse, examine how the design of popular digital wellbeing apps mitigate mobile phone use, and propose design features for future digital wellbeing apps.

Literature Review

The prevalence of Internet and social media addiction continues to increase in tandem with the growth in human dependence on technology. Estimates suggest that more than 210 million individuals around the world are suffering from this problem (Longstreet & Brooks, 2017), though whether such a phenomenon warrants the label “Internet Addiction Disorder” is contentious (Van Rooij & Prause, 2014). Nevertheless, the phenomenon of mobile phone overuse is palpable to parents, guardians, and educators. A 2010 study revealed that American youth spend an average of 7.5 hours per day on media consumption. This includes cell phones, computers, video games, TV, movies, music, and newspapers. Even younger children spend 2 hours per day with screen media (Rideout, Foehr & Roberts, 2010).

The causes of mobile phone overuse are multifaceted: a meta-analysis study conducted by Yıldız-Durak (2020) identified more than a dozen factors contributing to mobile phone overuse, including depression and stress, loneliness, social anxiety, interpersonal relationships, academic success, gender, self-esteem, and self-regulation. A complicating factor is that studies have shown an interplay between cognition and mobile phone overuse: while some studies have indicated that Internet addiction is linked with alterations of brain structure, others have discovered that executive functions have an effect on social media overuse (Cheng & Liu, 2020; Wegmann et al., 2020).

There is an increasing body of literature surrounding the effects of digital technologies on learning, attention, memory, and social interaction (Loh & Kanai, 2016). While the evidence is far from conclusive, some studies have demonstrated robust evidence of a negative impact of digital media multitasking on cognition, psychosocial behavior, neural structure, and academic outcomes (Uncapher et al., 2017). On the other hand, researchers have noted an association between higher levels of technology multitasking and higher levels of multitasking performance (Matthews, Mattingley & Dux, 2022), higher screen time and better working-memory-specific and shifting-specific executive function abilities (Toh et al., 2021), as well as an association between gaming and improved capacity to multitask (Anguera et al., 2013).

Design Principles Contributing to Mobile Phone Overuse

The increasing prevalence of mobile phone overuse has raised ethical concerns, yet technology users remain largely oblivious to its pervasive influence on their lives. This phenomenon can be attributed to the so-called “attention economy,” wherein social media platforms are designed to foster addiction through the intentional exploitation of human psychology (Bhargava & Velasquez, 2021). Consequently, users are increasingly captive to the persuasive powers of these platforms, allowing them to dominate their attention and affect their behavior.

The design principles behind the addicting elements of mobile phone apps have been extensively studied in recent years. Table 1 displays an overview of design principles that are believed to be contributors to mobile phone overuse.

Table 1

An overview of design principles contributing to mobile phone overuse

| Author(s) | Design principles contributing to mobile phone overuse |

|---|---|

| Montag et al. (2019) |

|

| Alutaybi et al. (2019) |

|

| Eyal (2014) |

The “Hooked model”:

|

Montag et al. (2019) identified six psychological mechanisms built into popular social media apps and games. Endless streaming/scrolling refers to the feature of allowing users to scroll down endlessly or autoplaying similar videos in the hope of promoting further user immersion. This technique exploits users by producing a “flow” state, coined by Nakamura and Csikszentmihalyi (2002), which can produce a feeling of time distortion. The endowment effect (Kahneman, Knetsch, & Thaler, 1991) posits that the more time a user invests in a given smartphone app, the harder it is for them to detach from the app. The mere exposure effect (Zajonc, 2001) states that the more often a user is exposed to a certain app, the more they will like it. Social pressure is a form of design that encourages users to interact with others within an app, such as the “double tick function” in WhatsApp, which nudges users to read and reply to messages, or guilds in game apps that encourage players to meet at a certain time online to go on a mission together (Thaler & Sunstein, 2009). Additionally, designers can show users what they like based on analyzing what posts they have “liked” and how long they hover over certain posts (Rader & Gray, 2015). Social reward, which refers to the mechanism by which users experience stronger activity in the ventral striatum (an area involved in the processing of rewards) after seeing their pictures receiving “likes” on social media apps (Sherman et al., 2016), is also employed. Finally, the Zeigarnik/Ovsiankina effect (Rickers-Ovsiankina, 1928) describes the phenomenon that individuals involved in the execution of high investment tasks will react with emotional strain if interrupted, and the final completion of the task will remove this strain. An example of this is players of the popular mobile app “Candy Crush Saga” who are motivated to solve difficult levels and may spend money buying additional “lives” in order to do so.

In their study on social media apps, Alutaybi et al. (2019) identified several persuasion triggers that contribute to the experience of Fear of Missing Out (FoMO). Among the most pervasive triggers is “fear of missing timely interaction”, which refers to the anxiety of not being able to interact or connect with other individuals within a specific period. Additionally, the study found that “fear of missing the sense of relatedness” is also a commonly reported trigger for FoMO, as it pertains to the need to continually check the group’s activity to stay informed about members and activities. Furthermore, Alutaybi et al. (2019) noted that “fear of missing the ability to be popular” is yet another factor that may induce FoMO, as it relates to the fear of not being able to achieve a desired image on social media and gain popularity among peers. Lastly, the study revealed that “fear of missing temporarily available information” is also a key trigger for FoMO, as it refers to a fear of not being able to view time-limited content, such as Snapchat stories or Instagram stories.

Eyal (2014) proposed the “Hooked model”, a four-phase model that utilizes behaviorist principles to explain the formation of habits through the use of mobile phone apps. The trigger phase is initiated by cues, which can be internal (e.g. boredom, pre-existing routines, loneliness) or external (e.g. notifications indicating a new message). The action phase is based on the Fogg (2009) behavior model, which posits that when motivation and ability are present, an action can occur. Social media platforms often increase the ability to take action by providing personalized recommendations and other incentives that may motivate users to pursue social acceptance. The reward phase reinforces user behaviors by providing rewards for actions taken, such as comments and “likes” on posts, or endless scrolling of news feeds. Finally, the investment phase increases the likelihood of users returning to social media platforms as they have invested value through content and followers, which is consistent with the “endowment effect” (Kahneman, Knetsch, & Thaler, 1991). This cycle of triggers, actions, rewards and investments results in an addictive feedback loop, where rewards and investments incentivize users to respond to triggers and perform actions, thus producing more rewards and investments.

The growing prevalence of mobile phone overuse has prompted researchers to explore potential interventions, such as mindfulness exercises and digital wellbeing apps (Gorman & Green, 2016; Throuvala et al., 2020). The latter have been particularly effective due to their ability to track behavior and provide tips for promoting cognitive, emotional, and behavioral wellbeing (Bakker et al., 2016; Király et al., 2020). Studies have found that digital wellbeing apps are effective at supporting self-awareness and self-regulation, suggesting their use as a viable intervention for mobile phone overuse.

Evaluation of Digital Wellbeing Apps

Lyons et al. (2022) published an analysis of the top downloaded digital wellbeing apps. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 2, which provides an overview of the key features of these apps.

Table 2

An overview of the key features of popular digital wellbeing apps

| Gamification-based | Utility-based | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest | Hold | ActionDash | StayFree | Google Digital Wellbeing | |

| Gamification | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × |

| Real-world rewards | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × |

| Comparison with other users | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| Daily phone usage overview | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Application blocking | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Although there are numerous digital wellbeing apps available in the app store, the majority of them offer similar functionalities (Lyons et al., 2022). As such, the focus of this section is to select five digital wellbeing apps from the available options, with the goal of categorizing them into two distinct groups: gamification-based and utility-based.

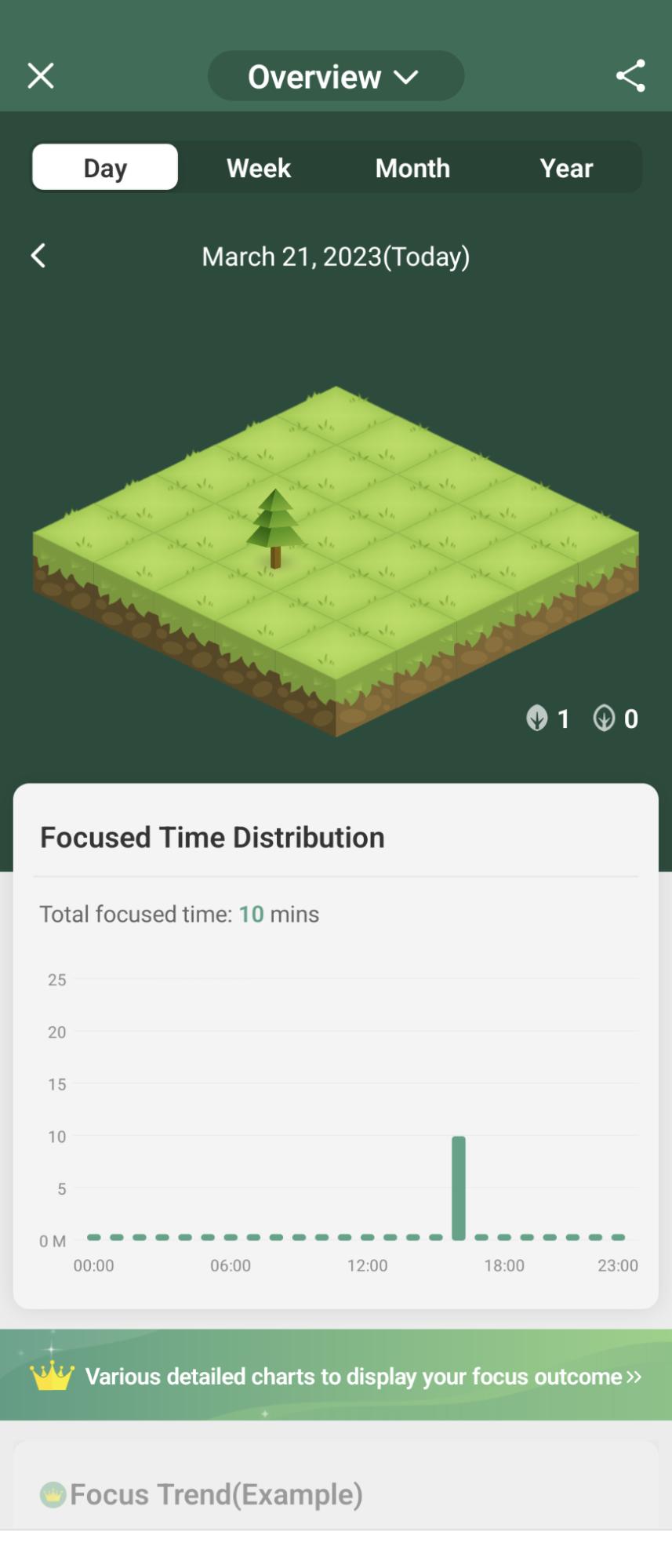

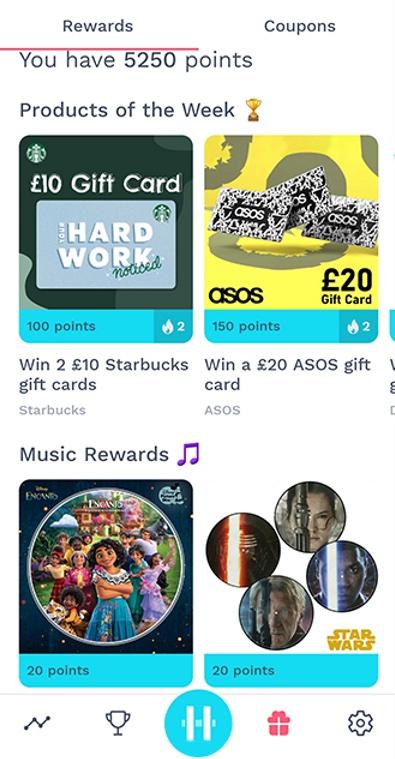

Gamification has become an increasingly popular technique used to encourage users to adopt certain behaviors. Two such apps that utilize this method are Forest and Hold, which both reward users for not using their phones. Forest rewards users by allowing them to grow virtual trees in a virtual forest (see Figure 1), while Hold allows users to earn points for not using their phone. Both apps function by allowing users to set a timer, after which the user will be blocked from using other applications on their phone; if the user stops the timer at any time, they will not be able to receive any rewards. Beyond virtual rewards (e.g. virtual trees and points), Forest and Hold offer users real-world rewards for not using their phone. For example, Forest users can use the virtual coins earned in the app to plant real trees in the world, while users of Hold can redeem their points for rewards such as Starbucks gift cards (see Figure 2).

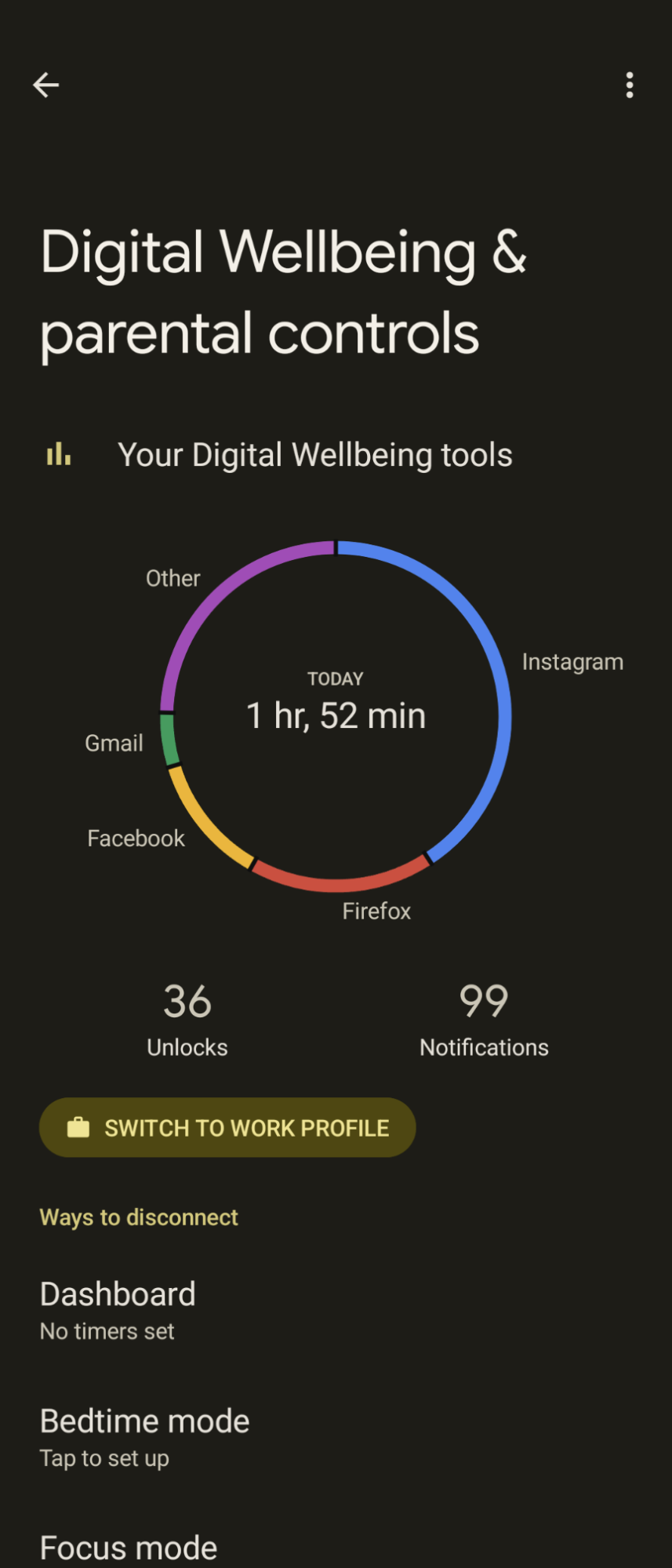

ActionDash, StayFree, and Google Digital Wellbeing are three free apps that offer users a range of functionalities to limit their usage of mobile devices. These apps mainly focus on providing a daily overview of phone usage and offer numerous ways to restrict app usage. For instance, ActionDash and StayFree present a time graph of when a user tends to use their phone most during the day (see Figure 3), whilst Google Digital Wellbeing shows a user’s engagement with their phone based on the time spent, number of unlocks, and notifications sent by applications (see Figure 4). All of the apps permit users to set a timer to confine the usage of certain applications, with some offering specific methods of app blocking. For example, ActionDash enables users to block app notifications, while StayFree allows users to block the launching of certain websites. Moreover, ActionDash and StayFree have built upon the game mechanic of competition by allowing users to compare their phone usage with that of other users.

Both gamification-based and utility-based digital wellbeing apps aim to counteract the design principles which contribute to mobile phone overuse. The function of blocking phone usage can prevent users from engaging in endless scrolling or streaming (Montag et al., 2019), while notification blocking inhibits triggers that would otherwise prompt the user to use their phone (Eyal, 2014). Moreover, by providing users with insight into the amount of time they have spent on certain applications, these digital wellbeing apps can foster reflection on phone usage habits and prompt users to reduce the use of certain mobile applications, potentially reducing the endowment effect and mere-exposure effect while they prompt users to reduce the use of specific mobile applications (Montag et al., 2019). Additionally, rewards of virtual and real-world varieties provided by gamification-based digital wellbeing apps can replace the reward systems of mobile phone applications (Eyal, 2014).

Nevertheless, these digital wellbeing apps seem to have failed to address some essential design principles contributing to mobile phone overuse. For instance, features which give social pressure for users to interact with other individuals and social reward in the forms of comments and “likes” (Alutaybi et al., 2019; Montag et al., 2019), features that induce Fear of Missing Out through temporarily available social media content (Alutaybi et al., 2019), and most importantly, internal triggers such as boredom and loneliness (Eyal, 2014).

Design features for future digital wellbeing apps

Despite their positive intentions of helping users break free of mobile phone overuse, digital wellbeing apps have been unsuccessful for some individuals, due in part to a lack of consideration of essential design principles which contribute to mobile phone overuse. This section will suggest design features which should be incorporated into future digital wellbeing apps in order to create more effective interventions for mobile phone overuse. These features include:

-

Whenever a user opens an app on their phone, they are prompted to record their intention for using the app and how much time they plan to spend using it.

Eyal (2014) argues that the trigger phase is the first step in the formation of habits through the use of mobile phone apps. However, many users are unaware of the reasons behind their use of such apps and may thus be prone to lose track of time due to the design of apps, which enables them to experience the state of “flow” through features like endless scrolling. For instance, a user may begin by intending to send a quick message on Instagram, but end up spending half an hour scrolling through their feed. To counter this, digital wellbeing apps should prompt users to consider their intention for using an app and the amount of time they plan to spend on it before opening the app. This could then lead to users being more conscious about becoming hooked to their mobile phone apps.

-

Whenever a user unlocks their phone, the positions of the apps on the phone screen are shuffled.

The habitual use of mobile phone apps during moments of boredom and loneliness is a common occurrence. People often subconsciously open apps due to the regular position of the apps on their phone screen. For example, it is common to observe people checking their Facebook feed or Instagram inbox while waiting for the bus or riding in an elevator, even though there is no explicit prompt to do so. To combat this habit, digital wellbeing apps should shuffle the position of apps on the phone screen whenever a user unlocks their device. This increased friction can provide the user with a moment of pause to consider their motives for opening a specific app.

-

Instead of filtering all notifications, show notifications to users in batches.

The “Do Not Disturb” mode on mobile phones is often used to reduce the amount of notifications received. According to the “Hooked model”, filtering notifications will remove cues which prompt users to open a mobile application (Eyal, 2014). However, research conducted by Fitz et al. (2019) has found that those who did not receive notifications at all experienced higher levels of anxiety and Fear of Missing Out (FoMO). In contrast, participants who had their notifications batched three times a day reported feeling more attentive, productive, in a better mood, and in greater control of their phones (Fitz et al., 2019). Therefore, it is recommended that digital wellbeing apps batch smartphone notifications three times a day to help improve psychological well-being.

-

Whenever the digital wellbeing app detects that the phone is within visible distance of the user, it will play a siren sound to remind the user to place it somewhere out of their sight.

The presence of one’s own smartphone has been found to reduce available cognitive capacity, according to research conducted by Ward et al. (2017). This suggests that simply placing a phone on the table with the screen down and turning it to silent may not be enough to help users stay focused on a task. To address this issue, future digital wellbeing apps may be developed to promote periods of separation from one’s phone. For example, these apps could make use of accelerometers to determine if the phone is placed in a stationary location, and use the microphone to determine if the phone is located in the same room as the user.

Conclusion

The interest in the issue of mobile phone overuse has led to a lot of research on design principles that are believed to be contributors to mobile phone overuse. Existing digital wellbeing apps available both for free and for purchase may not be effective interventions for the problem, as these apps often fail to address some of the most addictive features of mobile app designs, such as the use of social reward and social pressure. While the design features proposed in this paper for future digital wellbeing apps may not fully address all factors that can lead to mobile phone overuse, such as boredom and loneliness, these features possess the potential to reduce the negative effects associated with mobile phone use. Further research is necessary to determine the effectiveness of digital wellbeing apps in reducing mobile phone use and improving executive functioning. Nonetheless, these apps represent a starting point for those who wish to begin a “digital detox”.

References

Alutaybi, A., Arden-Close, E., McAlaney, J., Stefanidis, A., Phalp, K., & Ali, R. (2019, October). How can social networks design trigger fear of missing out? In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics (SMC) (pp. 3758–3765). IEEE.

Anguera, J. A., Boccanfuso, J., Rintoul, J. L., Al-Hashimi, O., Faraji, F., Janowich, J., ... & Gazzaley, A. (2013). Video game training enhances cognitive control in older adults. Nature, 501(7465), 97–101.

Bakker, D., Kazantzis, N., Rickwood, D., & Rickard, N. (2016). Mental health smartphone apps: Review and evidence-based recommendations for future developments. JMIR Mental Health, 3(1), e4984.

Bhargava, V. R., & Velasquez, M. (2021). Ethics of the attention economy: The problem of social media addiction. Business Ethics Quarterly, 31(3), 321–359.

Cheng, H., & Liu, J. (2020). Alterations in Amygdala connectivity in internet Addiction Disorder. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 2370.

Eyal, N. (2014). Hooked: How to build habit-forming products. Penguin.

Fitz, N., Kushlev, K., Jagannathan, R., Lewis, T., Paliwal, D., & Ariely, D. (2019). Batching smartphone notifications can improve well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 101, 84–94.

Fogg, B. J. (2009). A Behavior Model for Persuasive Design. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology. Presented at Claremont, California, USA.

Gorman, T. E., & Green, C. S. (2016). Short-term mindfulness intervention reduces the negative attentional effects associated with heavy media multitasking. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 1–7.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. H. (1991). Anomalies: The endowment effect, loss aversion, and status quo bias. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 193–206.

Király, O., Potenza, M. N., Stein, D. J., King, D. L., Hodgins, D. C., Saunders, J. B., ... & Demetrovics, Z. (2020). Preventing problematic internet use during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consensus guidance. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 100, 152180.

Loh, K. K., & Kanai, R. (2016). How has the Internet reshaped human cognition? The Neuroscientist, 22(5), 506–520.

Longstreet, P., & Brooks, S. (2017). Life satisfaction: A key to managing internet & social media addiction. Technology in Society, 50, 73–77.

Lyons, D., Kiyak, C., Cetinkaya, D., Hodge, S., & McAlaney, J. (2022). Design and development of a mobile application to combat digital addiction and dissociative states during phone usage. In IEEE International Conference on E‑Business Engineering (ICEBE) 2022.

Matthews, N., Mattingley, J. B., & Dux, P. E. (2022). Media-multitasking and cognitive control across the lifespan. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 4349.

Montag, C., Lachmann, B., Herrlich, M., & Zweig, K. (2019). Addictive features of social media/messenger platforms and freemium games against the background of psychological and economic theories. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(14), 2612.

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2002). The concept of flow. In Handbook of Positive Psychology (pp. 89–105).

Purohit, A. K., Barclay, L., & Holzer, A. (2020, April). Designing for digital detox: Making social media less addictive with digital nudges. In Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–9).

Rader, E., & Gray, R. (2015, April). Understanding user beliefs about algorithmic curation in the Facebook news feed. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 173–182).

Rickers-Ovsiankina, M. A. (1928). Die wiederaufnahme unterbrochener handlungen (Doctoral dissertation, Verlagsbuchhandlung Julius Springer).

Rideout, V. J., Foehr, U. G., & Roberts, D. F. (2010). Generation M2: Media in the Lives of 8‑ to 18‑Year‑Olds. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Sherman, L. E., Payton, A. A., Hernandez, L. M., Greenfield, P. M., & Dapretto, M. (2016). The power of the like in adolescence: Effects of peer influence on neural and behavioral responses to social media. Psychological Science, 27(7), 1027–1035.

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Penguin.

Throuvala, M. A., Griffiths, M. D., Rennoldson, M., & Kuss, D. J. (2020). Mind over matter: Testing the efficacy of an online randomized controlled trial to reduce distraction from smartphone use. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4842.

Toh, W. X., Ng, W. Q., Yang, H., & Yang, S. (2021). Disentangling the effects of smartphone screen time, checking frequency, and problematic use on executive function: A structural equation modelling analysis. Current Psychology, 1–18.

Uncapher, M. R., Lin, L., Rosen, L. D., Kirkorian, H. L., Baron, N. S., Bailey, K., ... & Wagner, A. D. (2017). Media multitasking and cognitive, psychological, neural, and learning differences. Pediatrics, 140(Supplement_2), S62–S66.

Van Rooij, A., & Prause, N. (2014). A critical review of “Internet addiction” criteria with suggestions for the future. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 3(4), 203–213.

Ward, A. F., Duke, K., Gneezy, A., & Bos, M. W. (2017). Brain drain: The mere presence of one’s own smartphone reduces available cognitive capacity. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 2(2), 140–154.

Wegmann, E., Müller, S. M., Turel, O., & Brand, M. (2020). Interactions of impulsivity, general executive functions, and specific inhibitory control explain symptoms of social-networks-use disorder: An experimental study. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 3866.

Yıldız‑Durak, H. (2020). Modeling of variables related to problematic internet usage and problematic social media usage in adolescents. Current Psychology, 39, 1375–1387.

Zajonc, R. B. (2001). Mere exposure: A gateway to the subliminal. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(6), 224–228.